Deceptively Simple

A Opinion in Prose Poetry

When a poem doesn’t work in verse, doesn’t leap or sing in ways that satisfy me, it is a sign that this particular piece may benefit from confinement. After all, it is in close proximity that the senses are heightened and felt more deeply; think seven minutes in heaven or being stuck in an elevator for several hours

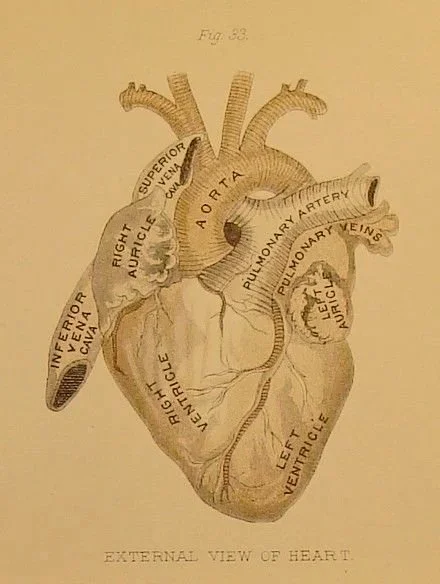

Suddenly, the heart becomes the most logical organ in the body simply for its consistency in beat.

If I had to have one contradictory opinion about prose poetry, it would be that narrative isn’t all that important. To be a bit of an extremist, I would say it is absolutely irrelevant. That is the realm of flash fiction; to daunt in predestined order, to harrow on a path that is straight as an arrow. When a prose poem prioritizes chronology over sonic play, I find myself terribly disappointed, as if a writer has sacrificed poetry’s greatest advantage to appeal to an audience who thinks clarity is far more fun than the manipulation of language. Readers do not need to know everything, trust me.

In a dense prose brick, poems bend to margins and the mind must accept the challenge. Think of being in a room with a bouncy ball in hand; no matter what, that ball must return to your hand or continue to rattle the hermitage. In his essay on prose poetry, Charles Simic confesses that the form is close to two centuries old and has, until his writing on it, gone without a proper definition. Luckily for us, language has never been fixed, never been afraid to grow many heads and spout nonsense. In attempting a definition, Simic even confesses his obliviousness; all the prose poems in his book were accidents.

Charles Simic

circa whenever in a mock turtleneck

Only through pressure from an editor did the reluctant label of ‘prose poem’ find its way into his dialect. In my early writing days, a mentor pointed out that I tended toward a dense lyricism, a habit of constructing lines of exactly the same length. Born were the poems thick as doorstops and heavy as cement; sound was a necessary, active element. Through assonance, the leaps were possible then, to move with swift feet from image to image without reverence for the reader’s hand. I made a return to this form earlier this year, craving a margin to put me back in my place, to, as Donne said, to knock, breathe, shine, mend.

Simic states that poets suffer from an inability to change their way of seeing and I agree; we know little of how to surprise ourselves. In the present literary landscape, a narrative poem that checks the following boxes earns you a hoot and holler from the live studio audience: mention light’s provocative slant in the first stanza, find a trauma you can apathetically loot, shuck transformation for buzzwords instead. If prose poetry is meant to be a bastard child, meant as Simic said, to “[thumb] its nose at verse that is too willed and too self-consciously significant,” could someone tell me nowadays where that poetry is?

There are far more interesting shapes than narrative, ones that actually reflect both the conscious and subconscious. When did realism become more authentic than imagination; why must truth be seen when most of us know it through an inner sensation, through the ripples it sends along our skin. Simic too echoes this, expressing a longing “for poems in which imagination runs free and where tragedy and comedy can be shuffled as if they belonged in the same pack of cards.” As a prose poet, I do not care if you believe me. But I want you to enjoy the striptease, wholeheartedly.

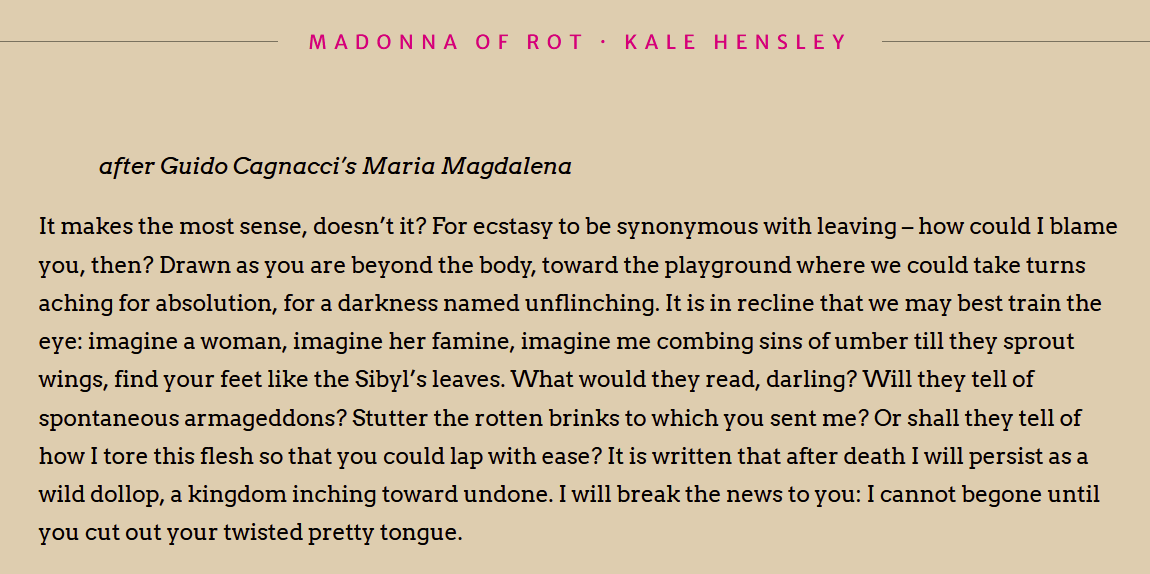

Many cite the distinguishing factor of prose poetry to be its inattention to line; this, I fear, is a lie. The lines do break and enjamb in the prose poem. The only difference is that the poet must relinquish some of their creative decisions to the margin. At times, I found myself thanking the margin for doing my dirty work, for showing me where to mince my language. In my poem “Madonna of Rot” (forthcoming in Nixes Mate Review), a gorgeously organic break arrives at the end of the poem, where the act of ‘cutting’ appears simultaneously in form and content:

featured in Issue 36-37 Summer-Fall 2025, Nixes Mate Review.

The piece attempts to capture the strange ecstasy of having an enemy and serve as an ekphrastic interpretation of Guido Cagnacci’s Penitent Magdalene. As Simic mentioned, the form aforementioned was an accident. When a poem isn’t resonating in verse, I tend to put it in the prose form to better understand its intentions and dimensions. In prose, I can ask it what it wants; to stay like this, it usually says. How contradictory, when trapped only then does the content discover its legs! Simic articulates the contradictory nature of the prose poem to be its strength, after all, it is a “monster-child of two incompatible impulses, one which wants to tell a story and another, equally powerful, which wants to freeze an image…for our scrutiny.”

Scrutiny, for me,

just doesn’t feel like the best word to describe this phenomenon; there’s a harsh sterility to this word that seems to profess the goal of writing is capture instead of wonder.

But perhaps that impulse to capture and observe is present, but not with malicious ends; instead, it is to fix my present self with the past and have an overdue conversation. As with “Madonna of Rot,” I needed to encounter the content in a container to understand its movements and aspirations–why does this series of questions yield imagery that is simultaneously dark and erotic?

The prose poem encourages a cyclical approach; the questions return with a tone that is far more accusatory and direct. The images, too in turn, become quite violent. With no place to go, the content resorted to “[tearing its] flesh” so that the ‘you’ “might lap with ease.” Once the body has been textually deconstructed, only does agency appear in the speaker’s voice–it was through confinement that somehow, the most necessary conclusion was achieved: the confession that this ‘you’ must also engage in the act of deconstruction to finally reach understanding about this turbulent relationship.

Through the ‘decreation’ of our bodies, only then do we lose this strange allegiance to social roles. We can analyze the parts of ourselves that are often missed when observing one’s image altogether. How paradoxical, that it took the unity of the prose form to illuminate the dissonance, to subtly gesture to this abundant need for closer analysis. I was not anticipating mysticism to appear in this essay, but I am not surprised. It seems to be the undercurrent of all my engagements these days. I knew prose was right for this piece when it organically ended with the line about the tongue severed from from the rest of the prose block; as if the gesture wanted to be illustrated in content and form.